24th Infantry Division (United States)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 24th Infantry Division was an infantry division of the United States Army. Before its most recent inactivation in 2006, it was based at Fort Riley, Kansas.

Formed during World War II from the disbanding Hawaiian Division, the division saw action throughout the Pacific theater, first fighting in New Guinea before landing on the Philippine islands of Leyte and Luzon, driving Japanese forces from them. Following the end of the war, the division participated in patrol operations in Japan, and was the first division to respond at the outbreak of the Korean War. For the first 18 months of the war, the division was heavily engaged on the front lines with North Korean and Chinese forces, suffering over 10,000 casualties. It was withdrawn from the front lines to the reserve force for the remainder of the war, but returned to Korea for patrol duty at the end of major combat operations.

After its deployment in Korea, the division was active in Europe and the United States during the Cold War, but saw relatively little combat until the Persian Gulf War, when it faced the Iraqi military. A few years after that conflict, it was inactivated as part of a post Cold War US military drawdown. The division was reactivated in 1999 as a formation for training and deploying Army National Guard units before inactivating again in 2006.

Contents |

History

Hawaiian Division

The 24th Infantry Division traces its lineage to Army units activated in Hawaii.[2] It was activated under the Square Division Table of Organization and Equipment (TO&E) on February 25, 1921 as the Hawaiian Division at Schofield Barracks, Oahu.[3] The division insignia is based on the taro leaf, emblematic of Hawaii.[4] The division was assigned the 21st Infantry Brigade[5] and the 22nd Infantry Brigade,[6] both of which had been assigned to the US 11th Infantry Division prior to 1921.

The entire Hawaiian Division was concentrated at a single during the next few years, allowing it to conduct more effective combined arms training. It was also manned at higher personnel levels than other divisions, and its field artillery was the first to be motorized.[3]

Between August and September 1941, the Hawaiian Division's assets were reorganized to form two divisions under the new Triangular Division TO&E. Its brigade headquarters was disbanded and the 27th and 35th Infantry regiments were assigned to the new 25th Infantry Division.[3] Hawaiian Division headquarters was redesignated as Headquarters, 24th Infantry Division on October 1, 1941.[2] The 24th Infantry Division also received the Hawaiian Division's Shoulder Sleeve Insignia, which was approved in 1921.[4]

The division was centered around three infantry regiments: the 19th Infantry Regiment and the 21st Infantry Regiment from the Active duty force, and the 299th Infantry Regiment from the Hawaii National Guard.[7] Also attached to the division were the 13th Field Artillery Battalion, the 52nd Field Artillery Battalion, the 63rd Field Artillery Battalion, the 11th Field Artillery Battalion, the 24th Signal Company, the 724th Ordnance Company, the 24th Quartermaster Company, the 24th Reconnaissance Troop, the 3rd Engineer Battalion, the 24th Medical Battalion, and the 24th Counter Intelligence Detachment.[7]

World War II

The 24th Infantry Division was among the first US Army divisions to see combat in World War II and among the last to stop fighting. The division was on Oahu, with its headquarters at Schofield Barracks, when the Japanese launched their Attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 and the unit suffered minor casualties during the attack.[8] The division was then charged with the defense of northern Oahu, where it built an elaborate system of coastal defenses throughout 1942.[8] In July 1942, the 299th Infantry Regiment was replaced by the 298th Infantry Regiment. One year later, this regiment was replaced by the 34th Infantry Regiment from the Hawaiian Department Reserve.[9] The 34th Infantry remained with the 24th Infantry Division until the end of the war. As an active component unit, the 34th was easier to deploy than the reserve component units, which were less trained.[7]

Indonesia

In May 1943, the 24th Infantry Division was alerted for movement to Australia, and it completed the move to Camp Caves, near Rockhampton, on the eastern coast of Australia by September 19, 1943. Once deployed, it began intensive combat training.[10] After training, the division moved to Goodenough Island on January 31, 1944, to prepare for Operation Reckless, the amphibious capture of Hollandia, Netherlands New Guinea (now Jayapura, Papua province, Indonesia).[11]

The 24th landed at Tanahmerah Bay on April 22, 1944 and seized the important Hollandia Airdrome despite torrential rain and marshy terrain.[10] Shortly after the Hollandia landing, the division's 34th Infantry Regiment moved to Biak to reinforce the 41st Infantry Division. The regiment captured Sorido and Borokoe airdromes before returning to the division on Hollandia in July.[10] The 41st and 24th divisions isolated 40,000 Japanese forces south of the landings.[12] Despite resistance from the isolated Japanese forces in the area, the 24th Infantry Division advanced rapidly through the region.[11] In two months, the 24th Division crossed the entirety of New Guinea.[13]

Leyte

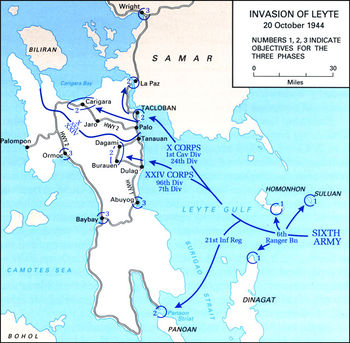

After occupation duty in the Hollandia area, the 24th Division was assigned to X Corps of the Sixth United States Army in preparation for the invasion of the Philippines. On October 20, 1944, the division was paired with the 1st Cavalry Division within X Corps, and the two divisions made an assault landing at Leyte,[14] initially encountering only light resistance.[15] Following a defeat at sea on October 26, the Japanese launched a large, uncoordinated counteroffensive against the Sixth Army.[16] The 24th Division drove up the Leyte Valley, advanced to Jaro and captured Breakneck Ridge on November 12, 1944, in heavy fighting.[10]

While final clearing operations continued on Leyte, the 24th Division's 19th Infantry Regiment moved to Mindoro Island as part of the Western Visayan Task Force and landed in the San Jose area on December 15, 1944.[10] There, it secured airfields and a patrol base for operations on Luzon. Elements of the 24th Infantry Division effected a landing on Marinduque Island. Other elements supported the 11th Airborne Division drive from Nasugbu to Manila.[10]

Luzon

The 24th Division was among the 200,000 men of the Sixth Army moved to recapture Luzon from the Japanese 14th Area Army, which fought delaying actions on the island.[17] The division's 34th Infantry Regiment landed at San Antonio, Zambales on January 29, 1945 and ran into a furious battle on Zig Zag Pass, where it suffered heavy casualties.[10] On February 16, 1945 the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry took part in the amphibious landing on Corregidor and fought the Japanese on the well-defended island. The rest of the division landed at Sablayan, Mindoro on February 19, cleared the remainder of the island and engaged in numerous mopping up actions during the following month.[18] These operations were complete by March 18, and the division moved south to attack through Basilan.[18] the division landed at Mindanao on April 17, 1945 and cut across the island to Digos until April 27, stormed into Davao on May 3, and cleared Libby airdrome on May 13.[10] Although the campaign officially closed on June 30, the division continued to clear up Japanese resistance during July and August 1945.[10] The 24th Infantry Division patrolled the region until the official surrender of Japan ended the war. On October 15, 1945 the division left Mindanao for occupation duty on mainland Japan.[10]

During World War II, members of the 24th Infantry Division won three Medals of Honor, 15 Distinguished Service Crosses, two Distinguished Service Medals, 625 Silver Star Medals, 38 Soldier's Medals, 2,197 Bronze Star Medals, and 50 Air Medals. The division itself was awarded eight Distinguished Unit Citations for participation in the campaign.[10]

Occupation of Japan

After the end of the war, the division remained on mainland Japan. It occupied Kyushu from 1945 until 1950.[19][20] During this time, the US Army shrank. At the end of World War II it contained 89 divisions, but by 1950, the 24th Infantry Division was one of only 10 active divisions in the force.[21] It was one of four understrength divisions on occupation duty in Japan. The others were the 1st Cavalry Division, 7th Infantry Division, and 25th Infantry Division, all under control of the Eighth United States Army.[22][23] The 24th Division retained the 19th, 31st, and 34th regiments, but the formations were undermanned and ill-equipped due to the post-war drawdown and reduction in military spending.[19]

Korean War

On June 25, 1950, 10 divisions of the North Korean People's Army launched an attack into the Republic of Korea in the south. The North Koreans overwhelmed the South Korean Army and advanced south, preparing to conquer the entire nation.[24] The United Nations ordered an intervention to prevent the conquest of South Korea. U.S. President Harry S. Truman ordered ground forces into South Korea. The 24th Infantry Division was closest to Korea, and it was the first US division to respond.[24] The 24th Division's first mission was to "take the initial shock" of the North Korean assault, then try to slow its advance until more US divisions could arrive.[20]

Task Force Smith

Five days later, on June 30, a 406-man infantry force from 1st Battalion, 21st Infantry Regiment,[25] supported by a 134-man artillery battery (also from the 24th Infantry Division) was sent into South Korea.[26] The force, nicknamed Task Force Smith for its commander, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Smith, was lightly armed and ordered to delay the advance of North Korean forces while the rest of the 24th Infantry Division moved into South Korea. On July 4, the task force set up in the hills north of Osan and prepared to block advancing North Korean forces.[26] The next day, they spotted an incoming column of troops from the North Korean 105th Armored Division. The ensuing battle was a rout, as the Task Force's obsolescent weapons were no match for the North Koreans' T-34 Tanks and full-strength formations.[26] Within a few hours, the first battle between US and North Korean forces was lost. Task Force Smith suffered 20 killed and 130 wounded in action.[26] Dozens of US soldiers were captured, and when US forces retook the area, some of the prisoners were discovered to have been executed.[27] Approximately 30 percent of task Force Smith became casualties in the Battle of Osan.[28] The task force was successful in delaying the North Korean forces' advance for seven hours.[29]

Pusan Perimeter

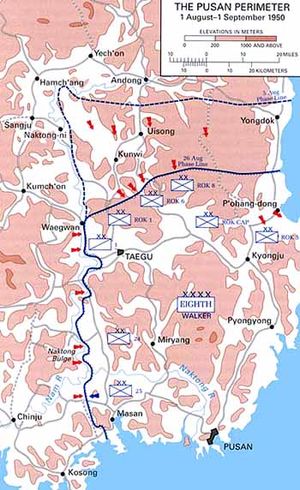

The 24th Infantry Division led the advance into South Korea, through the port of Pusan, and it followed by elements of the 1st Cavalry Division and 25th Infantry Division from the Eighth Army.[29] As more soldiers arrived, the 24th Infantry Division was placed under the command of I Corps, Eighth Army.[30] For the first month after the defeat of Task Force Smith, 24th Infantry Division soldiers were repeatedly defeated and pushed south by the North Korean force's superior numbers and equipment.[29][31] 24th Infantry Division soldiers were pushed south at and around Chochiwon, Chonan, Pyongtaek, Hadong, and Yechon.[29] The division's 19th and 34th regiments engaged the North Korean 3rd Infantry Division and the North Korean 4th Infantry Division[32] at the Kum River between July 13 and July 16 and suffered 650 casualties of the 3,401 men committed there.[29] The next day, the North Korean divisions attacked the 24th Infantry Division's headquarters in Taejon and overran it in the Battle of Taejon.[29][33] In the ensuing battle, 922 men of the 24th Infantry Division were killed and 228 were wounded of 3,933 committed there.[29] Many soldiers were missing in action, including the division commander, Major General William F. Dean, who was captured and later won the Medal of Honor.[29] On August 1, the 24th Division's 19th Infantry Regiment engaged North Korean forces, losing 90 killed.[29] North Korean officers at the battle claimed that some US soldiers were "too frightened to fight."[34] However, the 24th Infantry Division managed to delay the advancing North Koreans for two days, long enough for significant numbers of UN forces to arrive in Pusan and begin establishing defenses further south.[35] By the time the 24th Infantry Division retreated and reformed, the 1st Cavalry Division was in place behind it.[36] The division suffered over 3,600 casualties in the 17 days it fought alone against the 3rd and 4th North Korean divisions.[37]

By August 4, a perimeter was established around Pusan on the hills to the north of the city and the Naktong River to the west. The Eighth Army, including the 24th Infantry Division, was cornered by the surrounding North Korean army.[38] With UN forces concentrated and North Korean supply lines stretched out, the 24th Infantry Division halted the advance of the North Koreans.[39] The 24th Division was at Naktong, with the 25th Infantry Division to the south, and the 1st Cavalry Division and South Korean forces to the north. The 24th Division was also reinforced by the 2nd Infantry Division, newly arrived in the theater.[39] The 24th was quickly sent to block the North Korean 6th Infantry Division, which attempted to attack the UN forces from the southwest.[40] On August 8, the North Korean 4th Infantry Division crossed the river and attempted to penetrate the perimeter. After 10 days of fighting, the 24th Infantry Division counterattacked and forced the North Koreans back across the river.[39] By late August 1950, only 184 of the 34th Regiment's original 1,898 men remained. The regiment was dissolved and was replaced within the 24th by the 5th Regimental Combat Team.[41] The 34th Regiment's survivors were added to the ranks of the 19th and 21st regiments in an effort to bring them up to strength, and the 5th Infantry remained with the 24th Division until the division withdrew from Korea.[42] Elements of the 24th Infantry Division were moved into reserve on August 23 and replaced by the 2nd Infantry Division.[43] A second, larger North Korean attack occurred between August 31 and September 19, but the 2nd, 24th, and 25th infantry divisions and the 1st Cavalry Division beat the North Koreans back across the river again.[39]

At the same time, X Corps, with the 7th Infantry Division and 1st Marine Division, attacked Inchon, striking the North Korean army from the rear. The attack routed the surprised North Koreans, and by September 19, the Eighth Army pushed out of the Pusan Perimeter and advanced north.[44] The 24th Infantry Division advanced to Songju, then to Seoul.[45] The Army advanced north along the west coast of Korea through October.[44] By mid-October, the North Korean Army had been almost completely destroyed, and US President Harry S. Truman ordered General MacArthur to advance all units into North Korea as quickly as possible to end the war.[46] The 24th Infantry Division, with the South Korean 1st Infantry Division, moved to the left flank of the advancing Eighth Army, and moved north along Korea's west coast.[45] The 24th Division then moved north to Chongju.[47] On November 1, the division's 21st Infantry captured Chonggodo, 18 miles from the Yalu River and Korea's border with China.[44] Units of the Eighth Army and X Corps spread out as they attempted to reach the Yalu and complete the conquest of North Korea as quickly as possible.[46]

Chinese Intervention

On November 25, the Chinese entered the war in defense of North Korea. The People's Liberation Army force, which totaled 260,000 troops, flooded into North Korea and caught the Eighth Army by surprise.[48] Chinese forces crushed the UN and South Korean forces with overwhelming numbers, surrounding and destroying elements of the US 2nd Infantry Division, 7th Infantry Division, and South Korean forces.[49] The 24th Infantry Division, on the west coast of the Korean peninsula, was hit by soldiers from the 50th and 66th Chinese field armies.[50] Amid heavy casualties, the Eighth Army retreated to the Imjin River, south of the 38th parallel, having been devastated by the overwhelming Chinese force.[49]

On January 1, 1951, 500,000 Chinese troops attacked the Eighth Army's line at the Imjin River, forcing it back 50 miles and allowing the Chinese to capture Seoul.[49] The 24th Infantry Division was then reassigned to IX Corps to replace the 2nd and 25th Infantry Divisions, which had been placed in reserve due to heavy losses.[51] The Chinese eventually advanced too far for their supply lines to adequately support them, and their attack stalled.[52]

Stalemate

General Matthew B. Ridgway ordered I, IX, and X Corps to conduct a general counteroffensive on the Chinese (Operation Thunderbolt) quickly thereafter.[53] The 24th Division, as part of IX Corps, advanced along the center of the peninsula to take Chipyong-ni. The corps ran into heavy resistance and fought for the region until February.[54] Between February and March 1951, the 24th Infantry Division participated in Operation Killer, pushing Chinese forces north of the Han River.[55] This operation was followed by Operation Ripper, which recaptured Seoul in March.[56] After this, operations Rugged and Dauntless in April saw the division advance north of the 38th parallel and reestablish itself along previously established of defense, code named Kansas and Utah, respectively.[53]

In late April, the Chinese launched a major counterattack.[57] Though the 24th and 25th Infantry Divisions were able to hold their ground against the Chinese 9th CPV Army Corps, the South Korean 6th Infantry Division, to the east, was destroyed by the 13th CPV Army Corps, which penetrated the line and threatened to encircle the 24th and 25th divisions.[58] The 1st Marine Division and 27th British Commonwealth Brigade were able to drive the 13th Army Corps back while the 24th and 25th divisions withdrew on April 25.[59] The UN forces' line was moved back to Seoul but managed to hold.[59] In September, the UN forces launched another counteroffensive with the 24th Infantry Division at the center of the line, west of the Hwachon Reservoir.[60] Flanked by the South Korean 2nd and 6th Divisions, the 24th advanced past Kumwha, engaging the 20th and 27th CPV Armies.[60] In November, the Chinese attempted to counter this attack but were unsuccessful. It was at this point, after several successive counteroffensives that saw both sides fighting intensely over the same ground, that the two sides started serious peace negotiations.[61]

In January 1952, the 24th Infantry Division, which suffered over 10,000 casualties in 18 months of fighting, was redesignated as the Far East Theater reserve and pulled out of Korea.[19] It returned to Japan to rebuild. The 34th Infantry Regiment was reconstituted, and the division returned to full strength during the next year, having been replaced in Korea by the 40th Infantry Division of the California Army National Guard.[62] In July 1953, the division returned to Korea to restore order in prisoner of war camps. It arrived two weeks before the end of the war.[19]

The 24th Infantry Division suffered 3,735 killed and 7,395 wounded during the Korean War. It remained on front-line duty after the armistice until October 1957, patrolling the 38th parallel in the event that combat would resume. The division then returned to Japan and remained there for a short time.[19]

Cold War

On July 1, 1958 the division was relocated to Augsburg, Germany, replacing the 11th Airborne Division in a reflagging ceremony.[3] The 24th was organized under the Pentomic Division TO&E, in which its combat forces were organized into five oversized battalions (called "battle groups") with no intermediate brigade or regimental headquarters. Although considered an infantry division, the 24th included two airborne battle groups for several months.[3] The 1st Airborne Battle Group, 503rd Infantry left the division for reassignment to the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg on January 7, 1959[63] and the 1st Airborne Battle Group, 187th Infantry departed on February 8, 1959, also for the 82nd.[64]

On July 13, less than 2 weeks after the reorganization, King Faisal II of Iraq was assassinated in a coup orchestrated by pro-Egyptian officers. The Christian president of Lebanon, pressured by Muslims to join Egypt and Syria in the Gamal Abdel Nasser-led United Arab Republic, requested help from the Eisenhower administration during the 1958 Lebanon crisis.[65]

On the night of July 15, Marines of the Sixth Fleet landed at Beirut and secured the Beirut airport. The following day, the 24th Division's 1st Airborne Battle Group, 187th Infantry deployed to Turkey and flew to Beirut on the 19th.[65] They were joined by a medium tank battalion and support units, which assisted the Marines in forming a security cordon around the city. The force stayed until late October, providing security, making shows of force, including parachute jumps, and training the Lebanese army. When factions of the Lebanese government worked out a political settlement, they left. The 24th Division's 1/187th lost one soldier killed by a sniper.[65]

The 24th came into international press focus in 1961 when its commanding general, Major General Edwin Walker, was removed from command for making "derogatory remarks of a serious nature about certain prominent Americans ... which linked the persons and institutions with Communism and Communist influence".[66] The inquiry was sparked by Walker's "Pro Blue" program and accusations Walker and his Information Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Roberts, distributed John Birch Society literature as troop information in the 24th.[66]

After the construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961, the Seventh Army began sending infantry units from the divisions in West Germany on a rotating basis to reinforce the Berlin Brigade. The 24th Division's units participated in this action.

In January 1963, the 24th was reorganized as a mechanized infantry division under the Reorganization Objective Army Division (ROAD) TO&E, which replaced the pentomic battle groups with conventional-sized battalions organized in three combined arms brigades. The 169th Infantry Brigade, previously assigned to the 85th Infantry Division was redesignated the 1st Brigade, 24th Infantry Division.[67] The 85th Division's 170th Infantry Brigade was redesignated the 2nd Brigade, 24th Infantry Division.[67] The 190th Infantry Brigade, previously assigned to the 95th Infantry Division, became the 3rd Brigade, 24th Infantry Division.[68] In 1965, the 24th Infantry Division received its distinctive unit insignia.[4]

The 24th remained in Germany, specifically Augsburg, Munich until September 1968, when it redeployed its 1st and 2nd Brigades to Fort Riley, Kansas, as part of Exercise REFORGER while the division's 3rd Brigade was maintained in Germany.[67] As the US Army withdrew from Vietnam and reduced its forces, the 24th Infantry Division and its three brigades were inactivated on April 15, 1970 at Fort Riley.[5][6]

In September 1975, the 24th Infantry Division was reactivated at Fort Stewart, Georgia,[2] as part of the program to build a 16-division US Army force.[69] Because the Regular Army could not field a full division at Fort Stewart, the 24th had the 48th Infantry Brigade of the Georgia Army National Guard assigned to it as a round-out unit in place of its 3rd Brigade.[67] Targeted for a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) role, the 24th Division was reorganized as a mechanized division in 1979.[3] It was one of several divisions equipped with new M1 Abrams tanks and M2 Bradley Fighting Vehicles that formed the core of the US Army's heavily armored mechanized force for the 15 years that followed.[70]

Gulf War

Desert Shield

When the United Nations intervened in Kuwait in 1990, the 24th Infantry Division, which was part of the Rapid Deployment Force, was one of the first units deployed to Southwest Asia. It arrived in 10 large cargo ships of the US Navy Sealift Command.[71] Advance elements of the 24th Division began arriving in Saudi Arabia on August 17.[72] Some controversy erupted when the division's round-out unit, the 48th Infantry Brigade (Mechanized), of the Georgia National Guard, was not called up for service.[73] Army leaders decided that the use of National Guard forces was unnecessary, as they felt the active-duty force had sufficient troops.[74] The 48th Brigade was replaced once the 24th Division was in Saudi Arabia with the regular Army's 197th Infantry Brigade (Mechanized). The 24th Division was then assigned to XVIII Airborne Corps as the corps' heavy-armored division.[75] In the months that followed, the 24th Division played an important part of Operation Desert Shield by providing heavy firepower with its large number of armored vehicles, including 216 M1A1 Abrams tanks.[76] Elements of the division were still arriving in September, and in the logistical chaos that followed the rapid arrival of US forces in the region, the soldiers of the 24th Division were housed in warehouses, airport hangars, and on the desert sand.[77] The 24th remained in relatively stationary positions in defense of Saudi Arabia until additional American forces arrived for Operation Desert Storm.

Desert Storm

Once the attack commenced on February 24, the 24th Infantry Division formed the east flank of the corps with the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment.[78] It blocked the Euphrates River valley to cut off Iraqi forces in Kuwait and little resistance.[79] At this time, the 24th Division's ranks swelled to over 25,000 troops in 34 battalions, commanding 94 helicopters, 241 M1 Abrams tanks, 221 M2 Bradley Armored fighting vehicles, and over 7,800 other vehicles.[80] The 24th Infantry Division performed exceptionally well in the theater; it had been training in desert warfare for several years before the conflict.[80] On February 26, the 24th Division advanced through the valley and captured Iraqi airfields at Jabbah and Tallil. At the airfields, it encountered entrenched resistance from the Iraqi 37th and 49th Infantry Divisions, as well as the 6th "Nebuchadnezzar" Mechanized Division of the Iraqi Republican Guard. Despite some of the most fierce resistance of the war, the 24th Infantry Division destroyed the Iraqi formations[81] and captured the two airfields the next day. The 24th then moved east with VII Corps and engaged several Iraqi Republican Guard divisions.[82]

After the Iraqi forces were defeated, the UN mandated the US withdraw from Iraq, ending the Gulf War.[83] By the time of the cease-fire on February 28, the 24th Infantry Division advanced 260 miles and destroyed 360 tanks and other armored personnel carriers, 300 artillery pieces, 1,200 trucks, 25 aircraft, 19 missiles, and over 500 pieces of engineer equipment. The division took over 5,000 Iraqi prisoners of war while suffering only eight killed, 36 wounded, and five non-combat casualties.[84]

After returning to the United States in spring 1991, the 24th was reorganized with two brigades at Fort Stewart and the 3rd Brigade reactivated at Fort Benning, Georgia, replacing the 197th Infantry Brigade.[67] In fall 1994, Iraq again threatened the Kuwaiti border, and two brigades from the division returned to southwest Asia.[3] As part of the Army's reduction to a ten-division force,[85] the 24th Infantry Division was inactivated on February 15, 1996[2] and reflagged to become the 3rd Infantry Division. Its three brigades were reflagged as 3rd Infantry Division brigades.[67]

Training command

In the wake of the Cold War, the US Army considered new options for the integration and organization of Active duty, Army Reserve and Army National Guard units in training and deployment. Two active duty division headquarters were activated for training National Guard units; those of the 7th Infantry Division and the 24th Infantry Division.[86] The subordinate brigades of the divisions did not activate, so they could not be deployed as combat divisions. Instead, the headquarters units focused on full-time training.[87]

On June 5, 1999 the 24th Infantry Division was reactivated, this time at Fort Riley, Kansas.[2] From 1999 to 2006, the 24th Infantry Division consisted of a headquarters and three separate National Guard brigades; the 30th Heavy Brigade Combat Team at Clinton, North Carolina, the 218th Heavy Brigade Combat Team at Columbia, South Carolina, and the 48th Infantry Brigade Combat Team in Macon, Georgia.[3] The division headquarters was responsible for the Guard brigades should they be called to active duty in wartime. This never occurred, as each brigade deployed individually.[3] The division's final operations included preparing Fort Riley for the return of the 1st Infantry Division, which was stationed in Germany.

To expand upon the concept of Reserve component and National Guard components, the First Army activated Division East and Division West, two commands responsible for reserve units' readiness and mobilization exercises. Division East activated at Fort Riley.[88] This transformation was part of an overall restructuring of the US Army to streamline the organizations overseeing training. Division East took control of reserve units in states east of the Mississippi River, eliminating the need for the 24th Infantry Division headquarters.[88] As such, the 24th Infantry Division was subsequently deactivated for the last time on August 1, 2006 at Fort Riley.[89]

Though it was inactivated, the division was identified as the third highest priority inactive division in the United States Army Center of Military History's lineage scheme due to its numerous accolades and long history. All of the division's flags and heraldic items were moved to the National Infantry Museum at Fort Benning, Georgia following its inactivation.[90] Should the US Army activate more divisions in the future, the center will most likely suggest the first new division be the 7th Infantry Division, the second be the 9th Infantry Division, and the third be the 24th Infantry Division.[91]

Honors

The 24th Infantry Division was awarded five campaign streamers and one unit decoration in World War II, eight campaign streamers and three unit decorations in the Korean War, two campaign streamers for the Gulf War, and one unit award in peacetime, for a total of fifteen campaign streamers and five unit decorations in its operational history.[2]

Unit decorations

| Ribbon | Award | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philippine Presidential Unit Citation | 1944–1945 | for service in the Philippines during World War II | |

| Presidential Unit Citation (Army) | 1950 | for fighting in the Pusan Perimeter | |

| Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation | 1950 | for service in Pyongtaek | |

| Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation | 1952–1953 | for service in Korea | |

| Superior Unit Award | 1994 |

Campaign streamers

| Conflict | Streamer | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|

| World War II | Central Pacific | 1943 |

| World War II | New Guinea (with Arrowhead) | 1944 |

| World War II | Leyte (with Arrowhead) | 1945 |

| World War II | Luzon | 1945 |

| World War II | Southern Philippines (with Arrowhead) | 1945 |

| Korean War | UN Defensive | 1950 |

| Korean War | UN Offensive | 1950 |

| Korean War | CCF Intervention | 1950 |

| Korean War | First UN Counteroffensive | 1950 |

| Korean War | CCF Spring Offensive | 1951 |

| Korean War | UN Summer-Fall Offensive | 1951 |

| Korean War | Second Korean Winter | 1951–1952 |

| Korean War | Korea, Summer 1953 | 1953 |

| Gulf War | Defense of Saudi Arabia | 1991 |

| Gulf War | Liberation and Defense of Kuwait | 1991 |

Legacy

People who served in the 24th Infantry Division and later went on to achieve notability in the military or other fields include actor James Garner,[92] astronaut Charles D. Gemar,[93] the first Sergeant Major of the Army, William O. Wooldridge,[94] the sixth Sergeant Major William A. Connelly, the eleventh Sergeant Major Robert E. Hall, first Senior Enlisted Advisor to the Chairman William Gainey, science fiction author Tom Kratman, and Antulio Segarra, the first Puerto Rican to command an Army combat regiment.[95]

Many high-ranking generals served in the 24th Infantry Division before moving on to higher commands, including Generals Norman Schwartzkopf, John Hendrix, Barry McCaffrey, Burwell B. Bell III, David Petraeus,[96] Bernard W. Rogers,[97] Richard A. Cody, Wayne A. Downing, Bantz J. Craddock,[98] Paul J. Kern,[99] William R. Richardson, Volney F. Warner, Barksdale Hamlett[100] Sam S. Walker,[101] and Stanley A. McChrystal. Also serving in the 24th Infantry Division were Lieutenant Generals Paul E. Blackwell,[102] Thomas R. Turner II, Calvin Waller, William G. Boykin, Harry E. Soyster, Carl A. Strock, William J. Lennox, Jr., Ronald L. Burgess, Jr., John M. Brown III, James B. Vaught, and Michael Spiglemire, William G. Webster,[103] and Major Generals Eugene L. Daniel, Raymond Barrett, Antonio Taguba,[104] Guy C. Swan III, Walter Wojdakowski, and Jeffery Hammond.[105]

Fourteen soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor during their service with the 24th Infantry Division. Four soldiers received the Medal posthumously during World War II. They were James H. Diamond, Charles E. Mower, Harold H. Moon, Jr., and Francis B. Wai.[106][107][108][109] Wai originally received the Distinguished Service Cross, but it was upgraded during a 1998 review of war records of Asian-American and Pacific Islander soldiers. Another ten soldiers earned the medal in the Korean War. They were William F. Dean, George D. Libby, Melvin O. Handrich, Mitchell Red Cloud, Jr., Carl H. Dodd, Nelson V. Brittin, Ray E. Duke, Stanley T. Adams, Mack A. Jordan, and Woodrow W. Keeble.[110] Keeble's medal was awarded on March 3, 2008, 26 years after his death.[111]

Notes

- ↑ "Regular Army / Army Reserve Special Designation Listing". United States Army Center of Military History. 2009. http://www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/spdes-123-ra_ar.html. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "Lineage and Honors Information: 24th Infantry Division". United States Army Center of Military History. http://www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/lineages/branches/div/024id.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 "24th Infantry Division: "Victory Division"". globalsecurity.org. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/24id.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "The Institute of Heraldry: 24th Infantry Division". The Institute of Heraldry. http://www.tioh.hqda.pentagon.mil/Inf/24th%20Infantry%20Division.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 McGrath, p. 166.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 McGrath, p. 167.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Almanac, p. 592.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Almanac, p. 526.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the 34th Infantry Regiment". The Corregidor Historic Society. http://corregidor.org/rock_force/taromen/history.html. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 Almanac, p. 527.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Marston, p. 134.

- ↑ Horner, p. 48.

- ↑ Marston, p. 190.

- ↑ Horner, p. 56.

- ↑ Horner, p. 57.

- ↑ Horner, p. 59.

- ↑ Pimlott, p. 206.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Pimlott, p. 207.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Varhola, p. 97.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Alexander, p. 52.

- ↑ Stewart, p. 211.

- ↑ Stewart, p. 222.

- ↑ Catchpole, p. 41.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Varhola, p. 2.

- ↑ Alexander, p. 55.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Varhola, p. 3.

- ↑ Hackworth, David H. and Sherman, Julie, About Face: The Odyssey of an American Warrior, New York: Simon and Schuster (1989) ISBN 0671526928 p. 123.

- ↑ Appleman, Roy E. (2000). U. S. Army in the Korean War: South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu. United States Army Center of Military History. p. 58. ISBN ASIN B000YHKMUM.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 29.8 Varhola, p. 4.

- ↑ Varhola, p. 87.

- ↑ Alexander, p. 90.

- ↑ Alexander, p. 79.

- ↑ Alexander, p. 92.

- ↑ Malkasian, p. 24.

- ↑ Catchpole, p. 20.

- ↑ Alexander, p. 93.

- ↑ Alexander, p. 107.

- ↑ Varhola, p. 5.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 Varhola, p. 6.

- ↑ Alexander, p. 110.

- ↑ Varhola, p. 103.

- ↑ Varhola, p. 98.

- ↑ Malkasian, p. 26.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Varhola, p. 10.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Catchpole, p. 57.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Stewart, p. 230.

- ↑ Catchpole, p. 78.

- ↑ Varhola, p. 13.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Varhola, p. 14.

- ↑ Malkasian, p. 31.

- ↑ Varhola, p. 89.

- ↑ Varhola, p. 15.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Varhola, p. 16.

- ↑ Varhola, p. 17.

- ↑ Varhola, p. 18.

- ↑ Varhola, p. 19.

- ↑ Malkasian, p. 41.

- ↑ Catchpole, p. 120.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Malkasian, p. 42.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Malkasian, p. 50.

- ↑ Malkasian, p. 53.

- ↑ Varhola, p. 100.

- ↑ "US Army History: 503rd Infantry". US Army. http://www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/lineages/branches/inf/0503in001bn.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ↑ "US Army History: 187th Infantry". US Army. http://www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/lineages/branches/inf/0187in001bn.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 Olinger, Mark A. (May-June 2005). "Airlift operations during the Lebanon crisis: airlift of a Marine Corps battalion to Lebanon demonstrated that deploying contingency forces from the continental United States to an overseas operation was feasible and expeditious". Army Logistician. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0PAI/is_3_37/ai_n13783944. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Schoenwald, Jonathan M. (2001). A Time for Choosing: Extremism and the Rise of Modern American Conservatism, 1957-1972. Oxford University Press. pp. 100, 105–6. ISBN 0195134737. http://books.google.com/?id=uPZXEkMA0qQC&pg=PA100&dq=%22edwin+walker%22+%22pro+blue%22+%22john+birch%22. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 67.3 67.4 67.5 McGrath, p. 190.

- ↑ McGrath, p. 191.

- ↑ McKenney, p. 8.

- ↑ Kraus and Schubert, p. 70.

- ↑ Kraus and Schubert, p. 91.

- ↑ Kraus and Schubert, p. 55.

- ↑ Kraus and Schubert, p. 71.

- ↑ Kraus and Schubert, p. 72.

- ↑ Kraus and Schubert, p. 53.

- ↑ Kraus and Schubert, p. 56.

- ↑ Kraus and Schubert, p. 67.

- ↑ Stewart, p. 421.

- ↑ Stewart, p. 422.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Kraus and Schubert, p. 176.

- ↑ Krause and Schubert, p. 189.

- ↑ Kraus and Schubert, p. 175.

- ↑ Stewart, p. 423.

- ↑ Kraus and Schubert, p. 196.

- ↑ McKenney, p. 10.

- ↑ "Memorandum for Reserve Component Command". United States Army Forces Command. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/policy/army/acrc/96-10.doc. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- ↑ "Report to the Secretary of Defense (2000)". United States Department of Defense. http://www.dod.mil/execsec/adr2000/army.html. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 "First Army Division West: About Us". First United Stated Army Public Affairs. http://www.hood.army.mil/div_west/. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ↑ "Senator Roberts welcomes Big Red One home to Kansas". Kansas State Government. http://roberts.senate.gov/08-01a-2006.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-25.

- ↑ McKenney, p. 21.

- ↑ McKenney, p. 22.

- ↑ Rubin, Steve (1993). Documentary: Return to 'The Great Escape. MGM Home Entertainment.

- ↑ "NASA Biography: Charles Gemar". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/Bios/htmlbios/gemar.html. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- ↑ Elder, Dan (2003). The Sergeants Major of the Army. Center of Military History. p. 67. ISBN 978-0160678677.

- ↑ Hallahan, Robert F. (2003,). All Good Men: A Lieutenant's Memories of the Korean War. iUniverse,. p. 13,. ISBN 0595280188.

- ↑ "Petraeus set for another shot at Iraq". National Public Radio. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6952481. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- ↑ "Biography: Bernard W. Rogers". United States Army Center of Military History. http://www.history.army.mil/books/CG&CSA/Rogers-BW.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- ↑ "Bantz Craddock Biography". North Atlantic Treaty Organization. http://www.nato.int/shape/bios/saceur/craddock.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- ↑ "Command says goodbye to Four-star commander". US Army Materiel Command. http://www.amc.army.mil/amc/pa/releases04/kern.html. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- ↑ Johnston, Laurie (August 28, 1979). "Gen. Barksdale Hamlett, 70, Dies; Was a U.S. Commandant in Berlin". The New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F30A11F6345D12728DDDA10A94D0405B898BF1D3.

- ↑ "Arlington Cemetery entry for Sam Walker". Arlington National Cemetery. http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/whwalker.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- ↑ "Lt. General Paul E. Blackwell". http://www.strom.clemson.edu/events/calhoun/photos/blackwell/blackwell.html.

- ↑ http://www.northcom.mil/leaders_html/docs/Bio_Webster_may07.pdf

- ↑ "Major General Antonio M. Taguba". United States Army. 2003-12-10. Archived from the original on 2004-06-11. http://web.archive.org/web/20040611120931/http://www.arcent.army.mil/welcome/dcg_support.asp. Retrieved 2006-09-10.

- ↑ "Major General Jeffery W. Hammond, Commanding General, 4ID". Army Public Affairs Office, Fort Hood, TX. Archived from the original on 2008-07-15. http://web.archive.org/web/20080715131000/http://pao.hood.army.mil/4ID/leadership/commanders/cg.html. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ↑ "Medal of Honor Recipients — World War II (A-F)". United States Army. http://www.history.army.mil/html/moh/wwII-a-f.html. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ↑ "Medal of Honor Recipients — World War II (G-L)". United States Army. http://www.history.army.mil/html/moh/wwII-g-l.html. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ↑ "Medal of Honor Recipients — World War II (M-S)". United States Army. http://www.history.army.mil/html/moh/wwII-m-s.html. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ↑ "Medal of Honor Recipients — World War II (T-Z)". United States Army. http://www.history.army.mil/html/moh/wwII-t-z.html. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ↑ "Medal of Honor Recipients — Korean War". United States Army. http://www.history.army.mil/html/moh/koreanwar.html. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ↑ "President Bush Attends Medal of Honor Ceremony for Woodrow Wilson Keeble". The White House, Office of the Press Secretary. 2008-03-03. http://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2008/03/20080303-3.html. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

Sources

- Alexander, Bevin (2003). Korea: The First War we Lost. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0781810197.

- Catchpole, Brian (2001). The Korean War. Robinson Publishing. ISBN 978-1841194134.

- Horner, David (2003). The Second World War, Vol. 1: The Pacific. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0415968454.

- Kraus, Theresa L.; Frank N. Schubert (1995). The Whirlwind War: The United States Army in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. Diane Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0788128295.

- McKenney, Janice (1997). Reflagging the Army. United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN ASIN B0006QRJPC. http://www.history.army.mil/books/Lineage/reflag/fm.htm.

- Malkasian, Carter (2001). The Korean War. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1841762821.

- Marston, Daniel (2005). The Pacific War Companion: from Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima. Osprey Publishing. ISBN ASIN B002ARY8KO.

- McGrath, John J. (2004). The Brigade: A History: Its Organization and Employment in the US Army. Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-4404-4915-4.

- Pimlott, John (1995). The Historical Atlas of World War II. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805039290.

- Stewart, Richard W. (2005). American Military History Volume II: The United States Army in a Global Era, 1917-2003. Department of the Army. ISBN 978-0160725418.

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000). Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950-1953. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-1882810444.

- Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States. United States Government Printing Office. 1959. ISBN ASIN B0006D8NKK.